Multi-year watering provides and relies on cumulative progress over time. For example watering in one year may only wet a dry riverbed, but follow up watering the next year provides more water to fill the river and reach wetlands either side of the river where it waters plants and animals.

Multi-year priorities for native vegetation, waterbirds, native fish, and river flows and connectivity are listed below.

River flows and connectivity

Support lateral and longitudinal connectivity along the river systems

Many plants and animals in the Basin rely on river flows for water, food and habitat as well as to support the cycle of wetting and drying that underpins various stages of their life cycle.

Flows that reconnect main river channels with river tributaries (longitudinal connectivity) restore health to river systems by enabling animals to move, supporting nutrient and carbon cycling, and flushing salt downstream.

Connectivity between main river channels, wetlands and floodplains (lateral connectivity) restores river health by providing water to ecosystems for habitat, cycling nutrients through the river system, and providing natural cues for feeding, breeding and movement, which underpins the food web.

Support freshwater connectivity through the Lower Lakes, Coorong and Murray Mouth

The priority for river flows and connectivity is to improve connectivity between freshwater, estuarine and marine environments and to improve habitat conditions in the Coorong by optimising and managing inflows through the Lower Lakes and Murray Mouth.

The Coorong, Lower Lakes and Murray Mouth

The Coorong and Lakes Alexandrina and Albert (the Lower Lakes) is one of Australia’s largest wetland systems. It has 23 wetland types, covers 142,500 hectares and meets 8 of 9 criteria listed in the Ramsar Convention. It is an important feeding habitat for international migratory waterbirds like the curlew sandpiper. It also removes salt and sediment from the Basin through the Murray Mouth and allows native fish to move between marine, estuarine and freshwater environments.

Improving conditions in the Coorong requires a long-term approach. Many key species and ecological processes within the system need specific flow regimes over multiple years to begin to recover.

Connectivity between freshwater, estuarine and marine environments helps native fish move and migrate. This sustains populations and enables fish to complete life cycles in different aquatic environments. It is particularly important for diadromous fish – those which move between fresh and saltwater to breed. Some of these fish are congolli, common galaxias, short-headed lamprey and pouched lamprey.

Salinity

The salinity of the Coorong generally increases with distance from the Murray Mouth. This varies over time and in response to inflows from the River Murray through the Lower Lakes and barrages. It is also influenced by seawater flowing back through the Murray Mouth and into the Coorong.

Ensuring a salinity gradient exists along the length of the Coorong is vital for a diverse and healthy estuary and the broader ecology of the Coorong.

Native vegetation

Support lateral and longitudinal connectivity along the river systems

Many plants and animals in the Basin rely on river flows for water, food and habitat as well as to support the cycle of wetting and drying that underpins various stages of their life cycle.

Flows that reconnect main river channels with river tributaries (longitudinal connectivity) restore health to river systems by enabling animals to move, supporting nutrient and carbon cycling, and flushing salt downstream.

Connectivity between main river channels, wetlands and floodplains (lateral connectivity) restores river health by providing water to ecosystems for habitat, cycling nutrients through the river system, and providing natural cues for feeding, breeding and movement, which underpins the food web.

Allow opportunities for growth of non-woody wetland vegetation

Non-woody wetland vegetation are the grasses and herbs that occupy the shallow margins and surrounds of wetlands, or opportunistically inhabit dry-phase ephemeral wetlands. They include grasses, sedges, rushes, herbs and a variety of aquatic and amphibious species. These water-dependent plants require flooding for some or all of their life cycles in order to grow and reproduce. They can cover extensive areas with a single species, such as the Moira grass plains in the Barmah–Millewa Forest, or form highly diverse plant communities that shift in composition over time in response to wetting and drying cycles. Maintaining appropriate wetland inundation frequency and variability supports the persistence and ecological character of non-woody wetland vegetation communities.

Allow opportunities for growth of non-woody riparian vegetation

Non-woody riparian vegetation is comprised of a diverse range of soft-tissue plants that occur along banks and riparian areas of waterways. These groundcover plant communities often occur beneath riparian canopy species such as river red gum and contribute to species diversity and ecological character, habitat for a variety of aquatic and terrestrial animals, and protect riverbanks from damaging erosion during high flow events. Varying river flow rates support the growth and recruitment of non-woody riparian vegetation by providing periodic inundation and maintaining riparian groundwater levels.

Maintain the extent, improve the condition and promote recruitment of forests and woodlands

River red gum, black box and coolibah forests grow on riverbanks and floodplains. These forests provide habitat and resources for aquatic, amphibious and terrestrial animals. Forests contribute dissolved organic carbon into the nearby rivers. Roots and branches provide shelter and habitat for fish and help moderate water temperature by providing shade.

Water delivery to the floodplain in line with this priority will provide necessary water for saplings. It will also improve the condition of other understorey vegetation (i.e. shrubs and grasses) in these forests and woodlands. River red gum, black box and coolibah depend on flooding for growth and recruitment. This differs across species depending on their location on the floodplain.

Maintain the extent and improve the condition of lignum shrublands

Lignum grows along riverbanks, on floodplains and in wetlands across the Basin and can grow in woodlands under trees or as the dominant overstorey species in shrublands. Lignum shrublands provide important habitat and resources for a range of animal species, with dense, tall shrublands acting as ideal nesting and nursery habitat for many waterbird species during both wet and dry times.

Lignum requires periodic flooding to maintain good condition, promote growth and support reproduction. Lignum is found in a range of habitats which means that the lignum shrublands across the Basin experience a variety of inundation frequencies.

Expand the extent and improve the condition of Moira grass in Barmah–Millewa Forest

Moira grass is a rapidly growing, semi-aquatic grass that thrives in wetlands and floodplains. Barmah–Millewa Forest has one of the largest inland plains of Moira grass in Australia. The floodplain marshes are part of the Barmah Forest Ramsar Convention listing.

There has been a continual decline in the extent of, or the area covered by, Moira grass. Only around 182 hectares of Moira grass in the floodplain marshes in Barmah Forest was recorded in early 2014. This is about 12% of the amount recorded at the time of its Ramsar listing in 1982. Without environmental watering the Moira grass plains could be extinct in Barmah–Millewa Forest in a matter of years.

There are a number of other threats to Moira grass in Barmah–Millewa Forest, including grazing pressures (e.g. pigs, kangaroos and horses) and encroachment of river red gum and giant rush.

The Barmah–Millewa Forest is on the River Murray between the towns of Tocumwal, Deniliquin and Echuca. It acts as a drought refuge in an otherwise arid to semi-arid region. The forest supports threatened species of plants and animals. It is part of bilateral migratory bird agreements. These agreements include JAMBA, CAMBA, ROKAMBA and the Bonn Convention on Migratory Species.

Expand the extent and improve resilience of Ruppia tuberosa in the southern Coorong

The Lower Lakes and Coorong is one of Australia’s largest wetland systems. It has 23 wetland types, covers 142,500 hectares and meets 8 of 9 criteria listed in the Ramsar Convention. Ruppia tuberosa (ruppia), a submerged aquatic plant that was once widespread along the length of the southern Coorong, is a key indicator of the health of the Coorong and a defining component of the ecosystem’s ecological character. Many species in the Coorong, such as waterfowl and migratory waders, rely on the plant as a food resource. Ruppia also provides habitat for other species in the Coorong.

The condition and extent of ruppia ;is influenced by a range of factors, such as water levels, water quality and the presence of filamentous algae within the Coorong. The millennium drought had a significant impact on the condition of the species, with ruppia disappearing from the southern Coorong. Although the species is showing signs of recovery, providing suitable habitat conditions and flow regimes for ruppia is essential to maintain this species that underpins the ecology of the ecosystem.

Waterbirds

Maintain the diversity and improve the abundance of the Basin’s waterbird population

Restoring waterbird populations relies on successful breeding, a diversity of habitats in good condition and protection of drought refuges. The availability of breeding habitat and food resources is closely linked with wetland inundation, which will increase as more water is made available for the environment under the Basin Plan.

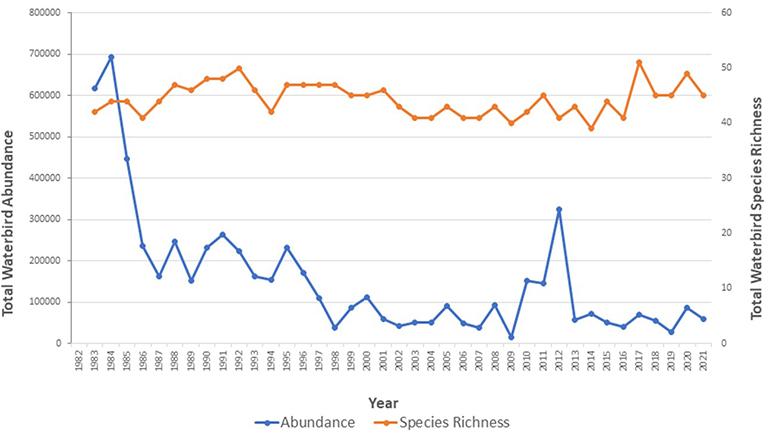

Waterbird abundance and species richness

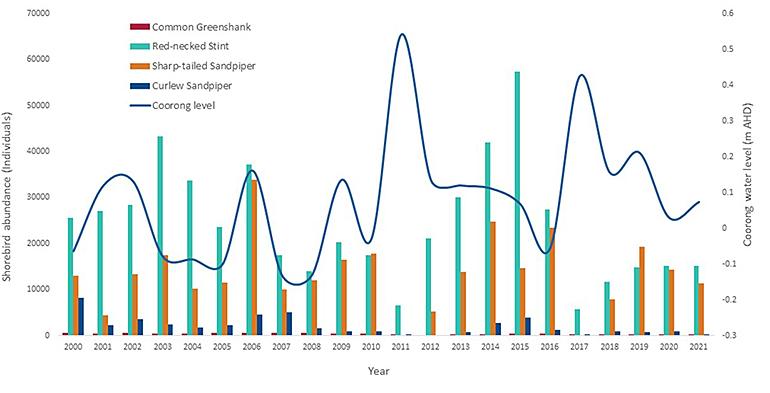

Maintain the abundance of key shorebird species in the Lower Lakes and Coorong

Maintaining the shorebird populations in the Lower Lakes and Coorong requires maximising the availability of productive foraging habitat during summer when migratory species are building body condition in preparation for their northward migration.

Graph below: Counts of curlew sandpiper, common greenshank, red-necked stint and sharp-tailed sandpiper and average Coorong water levels in January from 2000–2021 (Paton, 2021). As described in the Basin-wide environmental watering strategy, the four listed migratory shorebirds are at a minimum, to be maintained at levels recorded between 2000 and 2014.

Native fish

Support Basin-scale population recovery of native fish by reinstating flows that promote ecological processes across local, regional and system scales in the southern connected Basin

This priority focuses on providing suitable flows for species that live, and respond to flows, in river channels and anabranches. Flows that support fish recruitment processes in spring, summer and autumn will also provide food and habitat, and connectivity between habitats.

This will restore recruitment processes that promote population recovery of silver perch, golden perch, Murray cod and lamprey.

Four flow components are the focus of this priority:

- end-of-system flows through the barrage fishways and the barrages

- winter flows for food, habitat and connectivity between habitats within channels

- flows that support breeding activity in spring

- flows that support dispersal movements in spring, summer and autumn.

Improve flow regimes and connectivity in northern Basin rivers to support native fish populations across local, regional and system scales

This priority aims to improve native fish populations in the northern Basin by providing suitable flows and increasing connectivity within and between river systems. This will improve recruitment of native fish and allow fish to move between rivers.

The flow patterns of northern Basin rivers have always been variable. Recently, patterns of variation have changed, with an increasing number of cease-to-flow events and shorter periods when flows do occur. These changes are a contributing factor in the decline of the ecological health of the Barwon–Darling and its native fish communities.

To recover native fish in the Barwon–Darling and other northern basin rivers, it is important to protect environmental water and natural flows that drive recruitment processes. Returning suitable flow patterns will help northern Basin rivers to support native fish populations.

The 3 focus areas of this priority are:

- increase the frequency of flow types necessary to support native fish populations (e.g. base flows, freshes, bankfull and overbank flows)

- protect natural recruitment flows to boost native fish populations

- increase flow connections between the Barwon–Darling and its tributaries.

Support viable populations of threatened native fish, maximise opportunities for range expansion and establish new populations

Almost half of the native fish species in the Murray–Darling Basin are of conservation concern. Environmental watering, alongside other measures, is a key action to improve outcomes for threatened fish.

This priority seeks to protect remaining populations of threatened species and to increase the area(s) they occupy. Water managers are encouraged to work with threatened species recovery agencies to achieve the outcomes for this priority.

To increase the area that threatened species occupy and to build fish numbers, a number of steps can be taken in a process that spans multiple years:

- protect and boost key source populations

- support surrogate sites and populations that can start new permanent populations

- identify and prepare sites to establish permanent populations

- support fish stocked into reintroduction sites and secure their long-term future.

Last updated: 30 April 2025