It shares our current thinking on some of the Basin’s biggest and most complex challenges.

In it, we share how those areas of focus were considered when the Basin Plan was developed, what we’ve learned since then, and the changes we are considering to get better outcomes from the Basin Plan.

We have shared our early thinking on the Basin Plan Review to build understanding of key issues, so that everyone can participate fully in the consultation process in 2026.

We offer respect to the Traditional Custodians of Country in the Murray−Darling Basin and to their Nations. We pay our respects to Elders past and present.

We acknowledge their enduring deep Cultural, social, environmental, spiritual and economic connection to their lands and waters. First Nations people have been looking after Country in sophisticated ways for more than 65,000 years and continue to do so on behalf of their Nations and people.

We have heard many First Nations people express that when the lands and waters of Nations are not healthy, the people are unwell, and the ability to practice Culture and look after Country is impacted. This includes being able to swim in the local waterways and harvest traditional foods and resources.

First Nations people see waterways as living entities and live by the principle that everything is connected. Since colonisation, land, water and people have been separated. This goes against the way First Nations people see Country.

First Nations people in the Basin have been intentionally excluded from decision-making processes about water. Water management laws have contributed to disparity and dispossession, as they were developed without recognising First Nations’ sovereignty. We acknowledge that this causes distress.

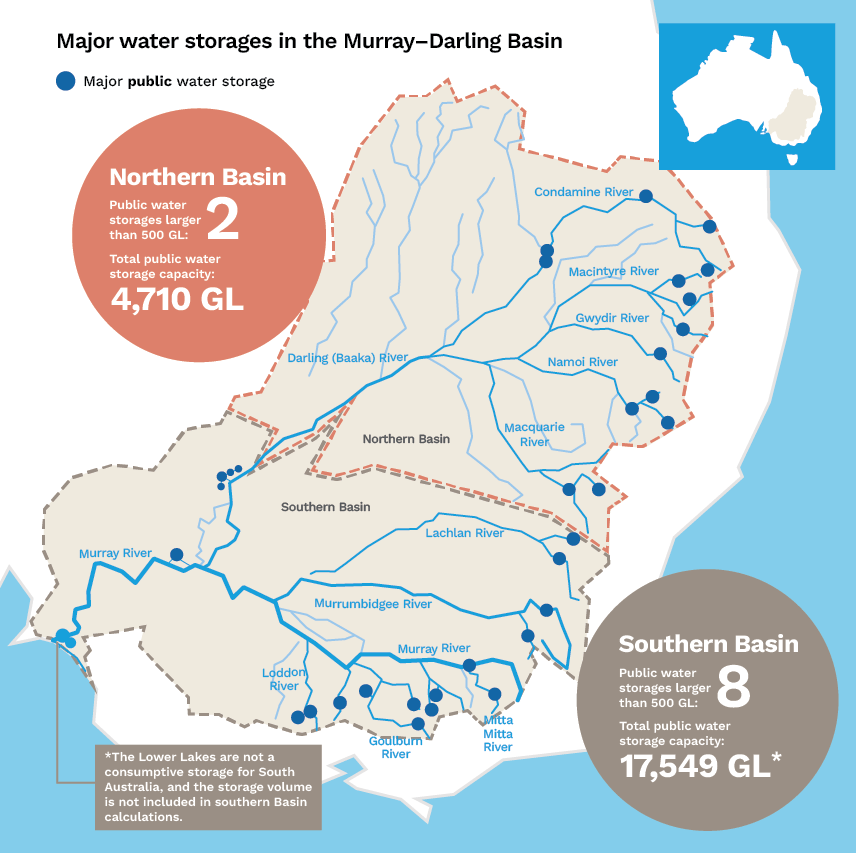

An error in Figure 4 has been corrected. The total number of water storages above 500 GL in the southern Basin is 8, and excludes the Lower Lakes. Further detail has been added to the figure.

Foreword

The Murray–Darling Basin is Australia’s largest river system. Over 77,000 kilometres of rivers and groundwater resources crossing 4 states and one territory. These provide water to our communities and environment. Ensuring the sustainability of the Basin is imperative.

In 2012, the Basin Plan introduced settings to address the degradation of the Basin. It was based on the best available information we had at the time.

Over the past 12 years, Basin communities have experienced drought, floods and increasing temperatures as greater climate variability associated with global climate change has made weather patterns less predictable. Agriculture has seen broadscale industry restructuring, swings in commodity prices, and dramatic changes to global export markets. These factors are beyond our immediate control. The Basin Plan, however, is within our control. We have the opportunity, through the Basin Plan Review, to ensure that the Basin Plan continues to adapt and keep pace with change and the challenges ahead.

In 2026, we will be delivering our first review of the Basin Plan. This review is not about starting again. It is important the current Basin Plan be delivered in full. We know that Basin Plan implementation activities – SDLAM supply projects, Northern Basin Toolkit, constraints relaxation, delivering of 450 GL of additional environmental water and water resource plan accreditation – are all critical actions needed to secure the health of our rivers.

The review is an opportunity to reflect on lessons learned, what’s working and what might need to change to support the Basin as our climate changes. This process will benefit from an improved knowledge base. With updated river models, a wide range of scientific knowledge and sources of evidence including lived experience, we will have access to one of the most advanced knowledge bases in the world for reviewing and improving river basin management. Our goal is to make the Basin Plan and its implementation more effective in a changing climate, and better enable Basin governments and communities to work together, ensuring the sustainability of our rivers for generations to come.

We acknowledge there are many drivers of change in the Basin. Through the Basin Plan Review, our focus is on supporting the delivery of Basin management outcomes including:

- healthy rivers that support resilient and thriving communities

- protecting key environmental systems and cultural assets

- protecting and promoting First Nations peoples’ rights, interests, and role as custodians for Country

- productive agriculture communities and confident industries.

Our role as an Authority is to lead, frame these challenges in a common language, and bring together and listen to diverse perspectives. This will better position us all to navigate the opportunities and trade-offs as we plan for the Basin’s future. The consequences of not working to achieve rivers for generations are significant. This challenge requires all of us to find a way to ensure a sustainable future, together.

We are committed to inclusive processes and see decision-making as a journey. We are unwavering in our commitment to fostering broad engagement and transparency throughout the Basin Plan Review. We know we get better outcomes when we work with our communities. We know that not everyone will agree with our recommendations, but we want to ensure that the process was fair and that the evidence base we used to inform our decisions was clear.

This Early Insights Paper is not a science report. Instead, it shares our current thinking on some of the Basin’s most complex challenges. It is part of our commitment to share the issues we are grappling with. Your thoughts and ideas will help shape the 2026 Basin Plan Review.

Yours sincerely

Air Chief Marshal Sir Angus Houston AK, AFC (Ret’d)

Chair, Murray–Darling Basin Authority.

Our approach to the 2026 Basin Plan Review

Context for the Basin Plan Review

During the late 1990s and early 2000s, much of the Basin was in a severe and prolonged drought. The Millenium drought pushed the Basin’s communities and environment to the limit. It was a signal that the management of the rivers in the Basin had to change. A cap on water extractions covered the Basin. But the cap was not based on sustainability considerations. It failed to address risks to water resources and stop further environmental harm.

In accordance with the Water Act 2007 (Cth) (the Water Act), the Basin Plan was brought into Commonwealth law in 2012. It was the result of a joint and agreed vision of the Australian Government and state and territory governments to manage the rivers and groundwater at the Basin scale in the national interest.

The Basin Plan has supported the achievement of Basin outcomes and objectives. It has led to a more consistent approach to water management across Basin governments. These outcomes were only possible because Basin governments worked together.

However, water recovery activities to implement the Basin Plan settings have divided the community. They sparked debates on the socio-economic impacts of water recovery. The relationship between these impacts and environmental benefits has been a key concern.

Developing and accrediting of water resource plans (WRPs) has been more complex and process oriented than expected. New South Wales (NSW) still has 6 WRPs not accredited almost 5 years past the 2019 deadline (as at 19 June 2024).

The Basin Plan created a formal process for First Nations people in water planning. It supported their voices, objectives and outcomes to be considered. Some First Nations are unhappy with how Basin governments and the MDBA have engaged with First Nations in the development and implementation of WRPs. Progress on outcomes for some First Nations has occurred where partnerships are strong. These include partnerships with state agencies, catchment management bodies and river operators, and environmental water holders. While beyond the remit of the Basin Plan, these partnerships are crucial. They, along with Basin government investments, are key to achieving the goals of First Nations and Basin management.

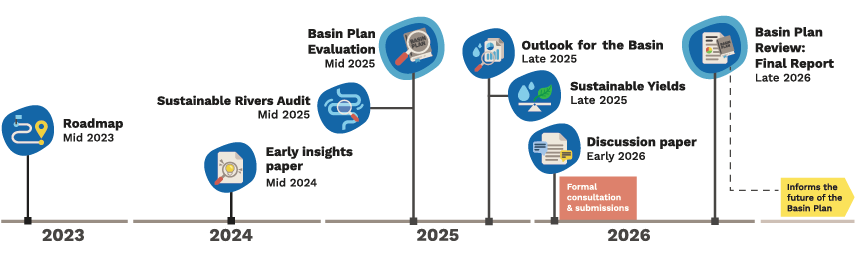

The Basin Plan Evaluation to be released in mid-2025 will provide a thorough assessment of Basin Plan implementation, its impact and its effectiveness to date. This will form the basis for the 2026 Basin Plan Review.

Taking an integrated approach to water management

The Basin Plan is part of a broader set of Basin management arrangements that includes river operations, environmental water management, land-use planning and natural resource management. In undertaking the review, we recognise that taking an integrated approach is important. This recognises that:

- Water for the environment is essential, but on its own is not sufficient: factors such as water quality, riparian and floodplain management, pest control, instream habitat, river operations, constraints and works, and environmental water portfolio management are crucial to secure environmental outcomes.

- Land and Basin water resources, including responding to climate change, are governed at multiple levels: these include local, regional, state and national and by different government and non-government bodies.

- Management planning, actions and their impacts occur across multiple timescales: we will look ahead to 2050 to understand what the future may hold for the Basin.

- Change might be needed to the broader regulatory and operational frameworks: this includes the Water Act and/or Murray–Darling Basin Agreement.

By adopting an integrated approach, the review can identify ways that the Basin Plan can improve its contribution to the achievement of Basin management outcomes.

Through the review, we can identify gaps between desired outcomes and existing governance processes, especially where the Basin Plan might usefully recognise where joint action is required.

This approach will also clarify policy areas where the Authority’s influence is limited and/or where we simply don’t have remit but we think change might be needed.

Our commitment to engage about decision-making

Our community has many perspectives when it comes to Basin management. This includes what constitutes a healthy Basin, and what outcomes the Basin Plan should support.

We see our decision-making as a journey. We are committed to a process of broad engagement, transparent process, and consultation throughout the Basin Plan Review process. We expect to make decisions and provide advice on potential changes to the laws, regulations and operations governing Basin water management, to ensure:

- Basin Plan settings, including Sustainable Diversion Limits (SDLs), continue to be effective in supporting environmental outcomes

- First Nations peoples’ rights and interests are protected in Basin Plan decision-making processes

- management of climate risks

- there is a process to adapt environmental outcomes where they are unsustainable under climate change

- the Basin Plan is an outcomes focused and effective regulatory framework.

The Water Amendment (Restoring our Rivers) Act 2023 has made First Nations rights and interests, and a response to climate risks, fundamental components of the Review.

The recommendations we make can affect our environment and impact Basin communities. If we are faced with challenging decisions involving trade-offs, we will consult communities and Basin governments to ensure we consider the broader context and provide an opportunity to test our findings before we decide and make recommendations. Following the Review, Basin governments will need to make decisions as to whether they implement any proposed changes.

When engaging with First Nations on the Basin Plan Review, we are aiming for inclusion and equity. Historically, we partnered with Murray Lower Darling Rivers Indigenous Nations (MLDRIN) and Northern Basin Aboriginal Nations (NBAN) to understand First Nations perspectives. We’re resetting how we engage with First Nations.

We’re ensuring all First Nations will have the opportunity to directly participate and express their views. Some First Nations have their own institutional capacity to work with governments and others. We will support other First Nations without this capacity where we can.

We are committed to an approach underpinned by the principle of Free, Prior and Informed Consent, and ensuring the Indigenous Cultural and Intellectual Property (ICIP) of First Nations is respected and protected.

To prepare for, and deliver the Review we will:

Assess the Basin Plan's effectiveness and share the evidence for our assessment (this includes identifying unanticipated outcomes)

Work with First Nations people across the Basin to ensure their rights and interests are accounted for in all parts of the review

Test our recommended options with communities for improvement

Be transparent and provide opportunities for engagement

Regularly share and publish our findings along the journey to the Final Report in 2026

How we will assess the effectiveness of Sustainable Diversion Limits

Sustainable Diversion Limits (SDLs) determine how much surface and groundwater can be taken by towns and communities, farmers and industries. Each area in the Basin has its own limit on water take for both ground and surface water.

We know that SDLs are of vital interest to communities. They affect environmental, cultural, social and economic outcomes. The setting and implementation of SDLs has local, Basin and national impacts.

We will evaluate the effectiveness of the SDLs in supporting desired Basin Plan environmental outcomes. In doing so, we will examine 2 timeframes:

- the next 10 years until the next scheduled review

- out to 2050.

We will identify any areas of immediate risk where we lack confidence in the achievement of outcomes in the next 10 years. If we assess that there is a risk to the ecological sustainability of some parts of the river system, we will explain to communities why our confidence is low. We will work with communities to understand major drivers of risk and explore what options are available to respond. In working through potential management response options, we will:

- consider a full range of measures (SDLs are critical but are not the only response to promote environmental outcomes, and we will consider both SDL and non-SDL options including effective management of environmental water and complementary measures)

- conduct robust environmental, social and economic analyses before proposing or recommending any responses (these will assess the relative impacts of different response options)

- consider what action is needed now and what types of additional monitoring is required for vulnerable and high-risk areas (monitoring thresholds can also help identify where action may be needed).

In undertaking this work, we will use the best available science and knowledge, taking a multiple lines of evidence approach. This includes using:

- information from regional long-term watering plans for each area, developed as part of Basin Plan implementation (we will use these to update and improve our understanding of how much water is needed to support key environmental assets, ecosystems, and functions across the Basin)

- updated river modelling

- updated condition and trend reporting

- First Nations science and knowledge shared with us

- hydroclimate information (this will enhance our understanding of the appropriateness of current arrangements and the impacts of climate change to the Basin’s water resources in the near term and out to 2050).

The assessment will assume the full implementation of the Basin Plan.

In early 2026, we will share the results of our assessment in the Basin Plan Review Discussion paper. We are committed to engaging on our decision-making processes with communities before making recommendations.

Climate change in the Basin

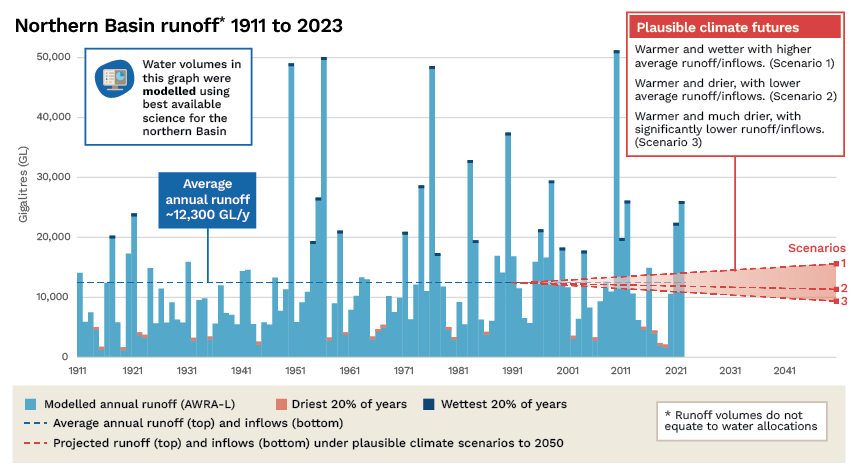

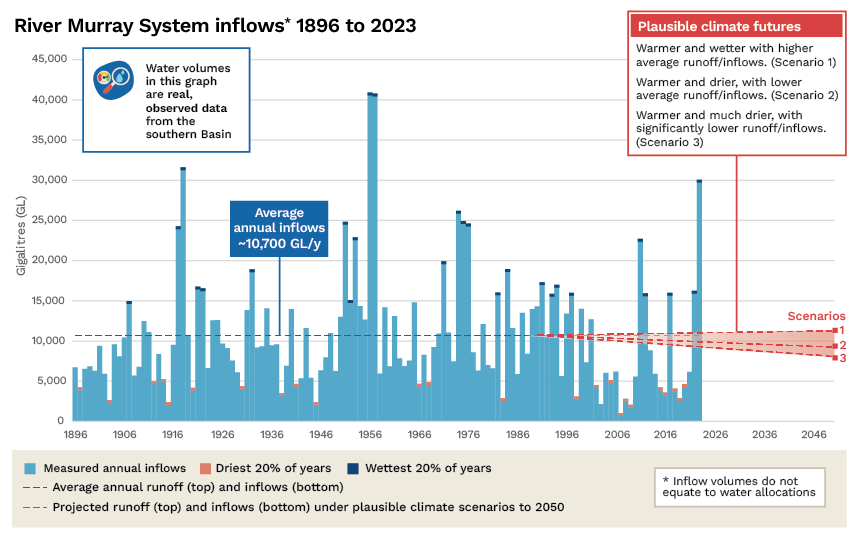

The Basin is warming because of global climate change. This will continue to have environmental, economic, social and cultural consequences for Basin communities. There is uncertainty in how, where, and when climate change will impact rainfall and runoff. However we expect that the southern Basin will have an underlying trend of declining water availability in the long-term. We may already be experiencing this. Twelve of our driest years occurred in the River Murray system between 1900 and 1997. The next 12 were experienced in the 22 years between 1998 and 2020.

Climate variability has always been a significant feature of the Basin’s water resources and management. As the climate changes, this variability is projected to increase. The severity and frequency of extreme weather events are expected to increase across the entire Basin.

Figures 1 and 2 show different projections for the northern and southern Basins. Projections for the northern Basin encompass both wetter and drier futures. The southern Basin may become much drier or maintain its historical state, but is unlikely to become wetter.

Climate science cannot predict the exact future we will have. However, it helps us understand the risks to Basin management outcomes. It can inform where action may be required now and where we need to be prepared in the future.

We have identified 6 key climate risks to the Basin from scientific studies and published papers involving the Basin and climate change:

Reduced ability for communities to meet their water needs due to reductions in water volume, reliability and quality, increased reliance on groundwater and higher temperatures

Adverse impacts to water-dependent ecosystems, habitats and environmental assets due to reductions in water volumes and quality, changes in timing and intensity of rainfall, and higher temperatures and extremes, combined with other environmental change and degradation.

Impacts on First Nations’ objectives and requirements such as spiritual, Cultural, customary, economic, heritage, water rights and interests, due to climate-related changes in river systems and environment, including depleted water supplies and increased water demand.

Adverse impacts on Basin employment and economic activities, particularly in the agriculture and tourism industries, due to rising temperatures and increased extractive water demand, coupled with increased variability and reductions in water availability, reliability, and quality.

Adverse impacts on the amenity, liveability, and livelihoods of Basin communities due to changes to stream flow, reduced water

quality, or climate-related changes in water-dependent environments.

Reduced ability to enjoy recreation or benefit from the economic or employment benefits of tourism and recreation activities in the Basin due to climate related changes to the condition of the river system and environment, including reductions in water volume, reliability and quality and/or higher temperatures.

The Review is an opportunity to better understand the potential consequences of long-term climate change for the Basin and consider how best to manage this transition, considering environmental sustainability, socio-economic wellbeing, and inter-generational equity.

Issues and opportunities

To invite your input and provide clarity on our decision-making process, we are sharing the issues we are grappling with. We’ve identified 5 areas of challenge:

Assessing the Basin Plan’s environmental outcomes

Preparing for a range of plausible climate futures

Moving beyond ‘just add water’

Managing the northern Basin

Building on, and simplifying the Basin Plan

These areas cut across the 4 themes for the 2026 review: Climate Change, First Nations, Sustainable Water Limits and Regulatory Design.

Assessing the Basin Plan’s environmental outcomes

The Review will use the knowledge gained over the past 12 years to assess the achievement of Basin environmental outcomes. This includes:

- updated river models

- updated condition and trend reporting

- First Nations science and knowledge shared with us

- hydroclimate information.

First Nations science and Basin condition knowledge will provide insight into the current context. Modelling, both using the historical inflow sequence and the potential impact of plausible future climates on water availability, will provide a long-term perspective of change.

Updated river models

River models have continued to improve as a planning support tool since 2012. Improvements include more accurate measurement of water take, recalibration of river gauges, incorporation of observed data and improved representation of rules, operations, environmental water management and water trade. We are working with Basin states to integrate these improved river models. Through the Integrated River Modelling Uplift Program and other means, we can increase transparency in the assumptions made in our modelling to avoid ‘black box’ decision-making.

Monitoring of condition and trend

A wide range of research and knowledge will inform the assessment of on-ground context of the Basin’s environmental assets and systems. This includes:

- 10 years of condition and trend reporting compiled by Basin states and territory governments

- more than 10 years of monitoring data from environmental watering activities in the Basin

- Basin-scale condition monitoring projects, including a Sustainable Rivers Audit (to be released in mid-2025).

Since 2012, the Basin has experienced extreme events including historically significant droughts and floods. Monitoring data collected over this period offers valuable insights into the resilience of the Basin’s environmental assets and the effectiveness of current Basin management.

First Nations peoples’ science and knowledge

First Nations science is led by First Nations people and respectfully interacts with the knowledge, observations and management of Country passed down through generations. We deeply value the sophisticated and long-term knowledge of Country that First Nations people hold.

The body of knowledge held by First Nations people can be viewed as an extensive living library containing intimate understandings of Country that intertwines land, water, people and the relationships between them. We are investing in and, respectfully and with consent, combining, First Nations and Western science and knowledge. We are seeking to work in partnership with First Nations people as part of the MDBA’s planning and decision-making processes.

As part of this approach, we are seeking to partner with First Nations people on Country across the Basin to support our understanding of the complex links between climate, flow and environment, and in doing so, enhance our collective understanding of these critical interactions to inform decisions.

Hydroclimate

To understand and respond to further impacts of climate change on Basin management, we will assess the extent to which Basin Plan environmental outcomes can be achieved under plausible future hydroclimates. To understand these plausible future hydroclimates, we will use a variety of sources, including natural history, meteorological observations, paleoclimate information and climate models. These will help build our understanding of how changes to water availability and water demand under climate change may impact the achievement of Basin environmental outcomes. As agreed with Basin government officials, we are working with experts to inform our hydroclimate methods for the Review.

Our challenge is to strike a balance between the different hydroclimate methods that could be applied, and what can usefully be modelled and interpreted to inform the Basin Plan Review in 2026. We will also consider the extent to which the selected hydroclimate method contributes to a consistent and integrated understanding of future Basin water availability. These assessments will be released as part of an updated Sustainable Yields study in late 2025.

Preparing for a range of plausible climate futures

Climate change poses a very real and present threat to our Basin. We know that the Basin Plan must change to support our ability to adapt to climate change. We are grappling with how the Basin Plan can better manage the detection of and response to undesirable conditions resulting from climate change.

Our assessment will grapple with risks to the achievement of Basin Plan environmental outcomes. We all need to ask the question: can these be better mitigated and responded to, or will some desired environmental outcomes not be sustainable under climate change?

For at-risk areas, the Review is an opportunity to identify response options to improve resilience. We also need to think about whether thresholds and triggers are needed to help make clear when attention is needed between 10-yearly reviews. These triggers could include, for example, when an environmental system is trending towards an undesirable state. For the 2026 review we are trying to understand critical change thresholds and ecological tipping points for the Basin.

Where the evidence suggests that in the future some environmental outcomes may no longer be sustainable, even after going through potential management response options, we will use the Basin Plan Review to kick off the next phase of adaptation. Where necessary, we will look to facilitate and help Basin governments and communities to work together on a process to potentially change environmental outcomes and/or propose new outcomes. These processes may take time because they involve hard, confronting conversations, but they are conversations we must have.

Local communities can play a crucial role in preparing for our climate futures. We are looking for opportunities for local involvement. Communities have valuable knowledge about how local river systems work and respond. They are well positioned to offer ideas and solutions to increase the resilience of the environment that they live in.

The Authority can enhance the local perspective with an integrated and cohesive view of Basin management. Basin-wide leadership from the Authority is critical, especially considering the potential for diversity in local processes, and scientific knowledge we hold regarding the overall health and outlook for the Basin.

Moving beyond ‘just add water’

Providing water for the environment has been essential to achieving Basin management outcomes, but ‘just adding water’ is not sufficient. Achieving Basin Plan environmental outcomes depends not only on the quantity of water for the environment, but on other legislation, rules and practices (see figure 3). These inform how:

- river operators run the river

- environmental water holders manage their portfolio

- land managers maintain and improve riparian areas.

River operations and delivering water for the environment

There are limitations in adding environmental water planning and delivery into a river management and operations framework designed for consumptive use. Over the past 20 years, river operators, environmental water holders and Basin communities have worked together to navigate the interactions between agreed historic river operation practices and environmental water delivery. Since the inception of the Basin Plan and the recovery of significant volumes of water for the environment, the interactions and limitations of integrating planning and delivery of environmental water with system planning have become more challenging.

Progress has been made in addressing physical constraints, as well as policy and operational impediments to managing our river systems in a way that better facilitates environmental outcomes, as well as outcomes for industry and communities.

For example, the timing and shaping of river flows using both system water and water for the environment has matured. Working with environmental water holders, new and existing river infrastructure has been trialled to deliver greater environmental benefits, often being able to achieve more environmental outcomes using less water. This has achieved mutually beneficial outcomes across the Basin for industry, community and the environment. This has only been possible through cooperative and productive approaches to working together.

Although progress has been made, the rules and governance for operating and managing our river systems are still largely structured for the management of water for consumptive use. With challenges such as climate change, evolving water policies and community expectations remains imperative. To continue to get better outcomes across the Basin that support the environment, we all need to collaborate.

Water quality

We have also experienced severe water quality events in both droughts and floods. Over the past 12 years, there have been multiple times in the northern Basin when water quality has been poor. This has had a significant impact on communities including First Nations people. There have also been mass fish deaths in the Lower Darling and around the Menindee Lakes due to poor water quality and low dissolved oxygen levels. The Basin Plan did not meaningfully influence the response to these events.

Holistic management of land and water

The Living Murray program, now in its 20th year, demonstrates the importance of integrating management of land and water to achieving environmental outcomes.

At The Living Murray icon sites, environmental water is supported by infrastructure works to deliver water for the environment. Complementary measures such as fencing and pest control have also contributed to environmental outcomes. Through the Indigenous Partnerships Program, First Nations whose traditional lands and water are within an icon site have had a meaningful role in the planning and management of these sites.

We need to better connect with riparian management, floodplain restoration and fish passage. These existing efforts are not as well connected to the Basin Plan as they could be.

First Nations have managed water holistically for more than 65,000 years, including during dynamic ever-changing climate challenges. Central to their approach is the understanding that water and land, in all their forms, are interconnected living entities.

First Nations people bring a sophisticated way of understanding Country. The recognition of First Nations science, knowledge and rights in land and water management can mutually benefit First Nations people and support Basin management outcomes. Strengthening partnerships between Basin state agencies and First Nations people has enabled First Nations people to set priorities and undertake monitoring, cultural heritage and land management works.

We recognise that Basin-scale environmental outcomes cannot be sustained without taking an integrated perspective.

To do so means:

- finding ways to reconcile, when required, the priorities of river operations and environmental water management

- effectively managing water quality not just quantity

- promoting a more holistic approach to land and water management.

The Water Act limits the Basin Plan to matters relevant to the regulation of water resources. It does not extend to the regulation of land use or planning.

We are grappling with how the Authority can ensure what we all know − that we get the best outcomes when rivers, land and water resources are managed together. The Authority’s role in the Review may be limited to connecting governments and communities to facilitate no-regrets actions. For example, Basin governments and communities need to continue to strengthen local land and water partnership initiatives. The Authority has facilitated these initiatives before, which has included the ‘Toolkit’ measures in the Northern Basin Review. The Authority could also exercise stronger leadership by proposing recommendations in the Review that incentivise Basin governments to take a more holistic approach to land and water management.

Managing the northern Basin

There are key differences between the northern and southern Basin. These include differences in rainfall patterns, the ability to regulate and store water and manage water flow, as summarised in the table on the next page. These differences directly impact how these systems are managed and ways that Basin management outcomes can be achieved.

The Basin Plan established SDLs and was a significant reform. The Basin Plan does not however fully acknowledge the fundamental differences in water management between the northern and southern Basin. It focuses on the sustainability of the Basin over time, not individual event management. Beyond setting stricter limits and ensuring stronger compliance, the Basin Plan has had limited influence in how Basin states have managed less regulated rivers in the northern Basin.

Over the past 12 years, the delivery of held environmental water, state-based rules and individual event management has been fundamental to improving flow connectivity, and ecological condition within and along the northern Basin’s rivers. We know that maintaining connectivity during drought, low flow regimes and resumption of flows are all critical.

In some cases, attempts to maintain connectivity and manage environmental water events using held environmental water has relied on the discretion of decision-makers for protection. Improved planning, communication and engagement regarding the use of rules to reconnect the system are necessary, as highlighted in an independent review of the 2020 Northern Basin First Flush event in NSW.

Increasing certainty by moving towards enduring arrangements rather than relying on temporary orders and restrictions can improve certainty for communities and the effectiveness of environmental watering events. Better environmental outcomes are secured by Basin states, communities and environmental water holders collaborating.

To complement state arrangements, the Basin Plan needs to focus on managing water across borders. In the northern Basin, this means ensuring Basin states manage flows through their rivers to contribute effectively to Basin-scale outcomes needed downstream.

Greater flexibility in the Basin Plan may be required to accommodate the different approaches to achieve Basin outcomes. In considering any improvements, we need to ensure the Basin Plan does not inhibit or restrict innovative rule development necessary to adapt to increased variability under climate change.

Table 1: Summary of the differences in water management between northern and southern Basins

| Northern Basin | Southern Basin | |

| Rainfall |

|

|

| River regulation and water storage |

|

|

| Ability to manage flow and 'call' water |

|

|

Building on, and simplifying the Basin Plan

The way that the Basin’s water resources are accounted for, managed and regulated through the Basin Plan is inherently complex. It is complex because the Basin Plan seeks to regulate how Basin governments manage the Basin’s water resources. Change to the Basin Plan is clearly required.

We want to simplify and improve elements of the Basin Plan to better support Basin management outcomes. This includes:

- water resource plan (WRP) development and accreditation processes

- the environmental watering management framework

- water quality management

- monitoring, evaluation and reporting processes.

We will focus on simplifying WRPs, which are crucial in SDL compliance. Accredited WRPs set the method for assessing use relative to the limits for each area. When the amount of water allocated exceeds what is sustainable and permitted, WRPs provide a basis for Commonwealth compliance and enforcement action.

Accrediting WRPs has increased confidence by establishing a common baseline for managing the Basin’s water resources. Assurance of water planning remains an important function of the Basin Plan. However, the prescriptive nature of WRP requirements has been raised by Basin governments as a barrier to amendment, innovation and improvement. In some cases, they hamper the ability to achieve better outcomes.

The next generation of WRPs must add value beyond the robust Basin state and territory water management arrangements by focusing on Basin-scale issues and risks. Our collective experience can inform this. For example, over the past 12 years there have been times where we have experienced a lack of system connectivity. WRP requirements could help Basin governments better coordinate water planning to support Basin management outcomes across river systems. We expect to identify further opportunities to improve and simplify the Basin Plan’s regulatory framework in the lead up to delivering the Review.

WRPs are required to ‘have regard to’ First Nations objectives and outcomes for water management (Chapter 10 Part 14 of the Basin Plan). This has provided an opportunity for First Nations people to engage with Basin governments. However, we have heard from First Nations people in the Basin about their extreme dissatisfaction with being siloed into ‘Chapter 10 Part 14’.

Concerns have been raised that there was inadequate regard to the views of First Nations people during the development of some WRPs, particularly around the risks to First Nations values and uses and cultural ties to land and water. While the processes that have been undertaken on accredited WRPs to-date have met the requirements of the Basin Plan, they have not necessarily supported better outcomes on the ground for First Nations people.

Some proposals to support improved First Nations outcomes are not within the scope of the Basin Plan framework. To get better outcomes for First Nations, we are strengthening relationships with First Nations and their people to support and enhance their involvement in decision-making and to better recognise their rights and interests.

How you can get involved, and how we will share our evidence

While we are delivering the Review in 2026, we have already started preparing. We’re engaging Basin communities about how to prepare for and conduct the Review.

There will be a range of opportunities to engage on what we’ve shared in this Early Insights Paper:

Contact a regional engagement officer

Call us on 1800 230 067

Send us an email: engagement@mdba.gov.au

Provide feedback using this online form

Subscribe to our newsletter River Reach for information on upcoming opportunities.

Over the next few years, your feedback will help shape our approach and inform our decisions.

We will release our knowledge base to share how the information we have gathered informs the Basin Plan Review − as set out in the timeline on the next page. This process is designed to ensure that the Review is informed by the best available scientific knowledge and socio-economic analysis.

In early 2026 we will release the Basin Plan Review Discussion paper. We will share which parts of the Basin Plan we are considering recommending for change. We will share the proposed changes and seek your feedback. You will be able to provide a formal submission in response to the Discussion paper.

The Final Report will set out and explain any recommendations for changes to the Basin Plan. Following the completion of the 2026 Review, the Authority may initiate a process for amending the Plan.

Basin Plan Review timeline

- Roadmap to the Basin Plan Review Mid 2023 – The Roadmap sets out the work we have planned. It shows how we’ll approach the next 3 years and tells you how you can get involved.

- Early Insights Paper Mid 2024 – We will share our early thinking on the Basin Plan Review to build understanding of the issues so everyone can participate fully in the consultation.

- Basin Plan Evaluation Mid 2025 – The Evaluation will play a critical role in tracking and communicating progress and achievement against the outcomes set out in the Basin Plan. The Evaluation will also identify potential improvements to the Basin Plan, which will inform the Basin Plan Review.

- Sustainable Rivers Audit Mid 2025 – The Sustainable Rivers Audit will examine the current environmental, social, economic and cultural condition and trajectory of the Basin under current water management practices. It will look at what is driving the changes we are seeing.

- Outlook for the Basin Late 2025 – Research will contribute to our shared understanding of the condition and trend of environmental, social, economic and cultural values in the Basin. We’ll assess risks to these values, and provide insights into the future condition of the Basin.

- Sustainable Yields Late 2025 – Providing a wholeof- Basin assessment of the likely impacts of climate change on the Basin’s surface water and groundwater resources, the Sustainable Yields study will ensure the Review is informed by the latest climate change science. This will produce assessments under a range of plausible climates out to 2050.

- Discussion paper Early 2026 – Using supporting knowledge and evidence we will outline options that we are considering, to support formal consultation.

- Basin Plan: Final Report Late 2026 – The final report will detail our view on the Basin Plan, and recommend changes for adaptive management of the Basin’s water resources into the future.

| Early Insights Paper downloads | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Publication title | Published | File type | File size | |

| Early Insights Paper | 03 Oct 2024 |

|

3.10 MB | |

| A summary of our Early Insights Paper | 19 Jun 2024 |

|

251.30 KB | |

Published date:19 June 2024